- Home

- Brassett, Pete

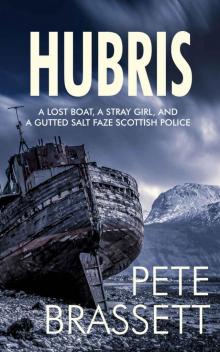

HUBRIS Page 7

HUBRIS Read online

Page 7

‘Is that not a wee bit unusual? I mean, would you not normally go to their house?’

‘He wanted to meet in the pub. He’s the client, he calls the shots.’

‘So, you like to give the personal touch?’

‘It’s a people business,’ said Boyd. ‘We’ve a reputation that’s grown by word of mouth, no advertising, no discounts, just quality work at a decent price.’

‘Good for you,’ said Duncan. ‘So, this chancer, he saw Henry’s bag and he thought he’d try his luck, is that it?’

‘I wasn’t there, but pretty much, aye.’

‘What kind of a bag was it? A plastic carrier from the supermarket? A holdall?’

‘A rucksack.’

‘And what was in it?’

‘Work stuff,’ said Boyd. ‘A few tools, a notebook, that kind of thing.’

‘Then why did Henry go off on one? I mean, for a few wee bits and bobs, he fair beat the fella half to death.’

‘Henry’s funny like that. He lives by his principles; thou shall not steal, and all that.’

‘I’m reminded of one myself,’ said Duncan. ‘Honour amongst thieves. Let’s get back to your fishing trip. You said you always hire a skipper when you charter the boat, and that’s because you know nothing about sailing, is that right?’

‘Aye, haven’t a scooby.’

‘And Henry?’

‘He can handle a pedalo, but that’s about it.’

‘So, unless it was honking down or blowing a gale,’ said Duncan, ‘you’d have no reason to be in the wheelhouse?’

‘None that I can think of.’

‘Then can you explain why your fingerprints are all over the cabin?’

Boyd, completely unruffled by the question, raised a hand to his chin and gazed pensively at the ceiling.

‘It was raining,’ he said, ‘not hard, just a wee drizzle as we rounded Arran. We may have stepped inside for a while.’

‘May have?’

‘Aye.’

‘And while you were inside,’ said Duncan, ‘would you have had cause to handle anything? Move things around?’

‘No, I told you, that’s why we have a skipper.’

‘I must be missing something, then,’ said Duncan, ‘because we found your prints all over a couple of wee computers sitting by the helm.’

‘Oh that,’ said Boyd. ‘I had to move the CP and the AIS so’s I had somewhere to sit.’

Duncan leaned across the desk, cocked his head, and frowned.

‘Sorry, Jack,’ he said, ‘you’ve lost me. The CP?’

‘The chartplotter,’ said Boyd, ‘and the Automatic Identification System. You’ll not get far without them.’

‘I’m impressed,’ said Duncan, his voice tinged with sarcasm, ‘but hold on there, I thought you knew nothing about piloting a boat.’

Boyd, for the first time in an otherwise flawless performance, dropped his guard and glanced furtively about the room.

‘I don’t,’ he said, bluntly. ‘It’s just words, you pick up the terminology when you’re surrounded by it.’

‘Aye, of course you do,’ said Duncan. ‘Now, about the skipper. Incidentally, his name’s Aron Jónsson by the way and get this, he’s not a Viking after all, he’s from Iceland.’

‘I’m made up for him.’

‘Okay, so you’re convinced Aron Jónsson took the boat while you and Henry were asleep in your pit, is that right?’

‘Who else would’ve taken it?’ said Boyd. ‘Not some ned, that’s for sure. It’s not a Subaru, Sergeant, it’s a clapped-out, old fishing boat.’

‘Did you not think to ask at the hotel if he’d checked out?’

‘What good would that have done?’

‘Well, did you not think to call him on his mobile?’

‘We didn’t have his number,’ said Boyd. ‘Why would we? We were with him twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week.’

‘Good answer. But would it not have made sense to call the police?’

‘We called McClusky,’ said Boyd. ‘We did everything we could.’

‘Unfortunately,’ said Duncan, ‘I’m not convinced you did. See here, Jack, I’ll tell you what I think. I think your story about getting the train back to Lockerbie is a complete pack of lies.’

‘Oh, aye? And how do you figure that?’

‘A wee thing called CCTV. You’re not on it. See here, Jack, I think you and Henry sailed the Thistledonia from Troon by yourselves. And I think you and Henry scuppered her deliberately off the coast of Lendalfoot.’

‘That’s quite a story,’ said Boyd, ‘but tell me this, even if we were on the boat, why would we want to scupper it?’

‘Because you couldn’t get rid of your passenger.’

‘Passenger?’

‘The skipper.’

Duncan paused as Boyd’s vacuous stare was interrupted by a tell-tale blink.

‘There’s something else, Jack,’ he said, lowering his voice. ‘I think you and your brother were also responsible for the attack on Aron Jónsson.’

Boyd hesitated for a moment, swallowed hard, then threw his head back and laughed theatrically.

‘You’re clutching at straws, now!’ he said, his shoulders twitching with mirth. ‘I mean, why exactly would we want to kill Aron Jónsson?’

Quietly elated by Boyd’s slip of the tongue, Duncan slowly stood, tucked his chair beneath the desk, and smiled.

‘Who said he was dead? In fact, Jack, how would you even know he was still on the boat?’

Enveloped by a deafening silence, Boyd cleared his throat, shook his head, and sighed despondently.

‘I can see I’m wasting my time here,’ he said. ‘We’re all entitled to our opinions, Sergeant, but yours are off the scale, so if we’re all done, then that’s me away. I’ve work to do.’

‘I hate to break it to you,’ said Duncan as he scrolled through his phone, ‘but work’s going to have to wait. Jack Boyd… bear with me, pal, this is a newbie for me. Oh aye, here we go. Jack Boyd, I’m arresting you on suspicion of violating the Merchant Shipping Distress and Prevention of Collisions Regulations 1996, and section 58 of the Merchant Shipping Act 1995, whereby you did wilfully cause the vessel known as the Thistledonia to run aground, and that you did also fail to report said incident to the Maritime Accident Investigation Branch. I believe that keeping you in custody is necessary and proportionate for the purposes of bringing you before a court where charges will be brought by the Maritime and Coastguard Agency. Do you understand?’

Boyd, his right foot tapping the floor, folded his arms and stared at Duncan with a supercilious smile smeared across his face.

‘No big deal,’ he said. ‘First, you have prove it, which I don’t believe you can, and secondly, even if you do, what’s the penalty for wrecking a boat? A wee fine? I can afford that, no problem. It’s not as if I’ll be going down for life.’

‘No, of course not,’ said Duncan, ‘not for that, anyway. But you will for murder.’

‘Are you joking me?’

‘Jack Boyd, under section 1 of the Criminal Justice Act I am also arresting you on suspicion of the murder of Aron Jónsson. You are not obliged to say anything but anything you do say will be noted and may be used in evidence. Do you understand?’

Chapter 9

Unlike the beautiful south where a sudden cold snap would render the roads impassable and send the snowflakes scurrying to the supermarket to panic-buy crates of avocados and artisan loaves, the weather in Caledonia, though prone to extremes, was best described as seasonal, with the most dramatic changes in the scenery occurring during the onset of winter when, despite the threat of plummeting temperatures, biting winds, and snow-laden clouds looming on the horizon, life went on as normal.

Cruising along the shore road, West, invigorated by a landscape worthy of an Ansel Adams, slowed to a sedate twenty to marvel at the sight of grey seals resting on the rocks where the stricken Thistledonia had lain less than thirty-six hours earlier bef

ore turning up the lane to the secluded farmhouse where Willy Baxter, standing beneath the front porch with his hands in his pockets, watched a uniformed officer make his way back to the patrol car.

West hopped from the Defender, flashed her warrant card, and smiled as PC Mark Villiers, disgruntled at having to leave the warmth of the office to listen to the ramblings of what he considered to be an over-protective parent, strode hurriedly towards her.

‘Alright?’ she said. ‘DI West, nice day for it. I thought you’d be long gone by now.’

‘So did I,’ said Villiers, scowling as he gawped at West wearing nothing but a white, cotton tee shirt beneath her biker jacket. ‘Are you not cold?’

‘Nah, I’m like an Arctic fox, me.’

‘I’m more of a reptile, myself. Are you here about the girl, too?’

‘Yeah, something like that. Have you got everything you need?’

‘Aye, I’d say so,’ said Villiers. ‘We’ll get her registered as missing then do the usual, you know, door-to-doors, then we’ll do a sweep of the area but we can’t go far, we don’t have the resources.’

‘What about her gaff?’ said West. ‘Have you got an address?’

‘Aye, but she lives in Stranraer so we’ll have to ask Dumfries and Galloway to take a look.’

‘Okay, do me a favour and ask them to have a gander as soon as they can. What about transport? Was she driving?’

‘No,’ said Villiers, ‘she’s not got a car, and she’s left her gear in the house. Her father seems to think she probably went for a walk and either took a fall or got lost, but I’m not convinced.’

‘Oh? Why’s that?’

‘She’s not a wean, miss, and she’s not a tourist. She’s an adult, and she’s a local. I’ll not be surprised if she’s back with her boyfriend or sleeping off a hangover with her pals.’

* * *

Baxter, unaccustomed as he was to receiving visitors, let alone those in uniform, regarded their brief exchange with a degree of trepidation before acknowledging West with a subtle nod of the head.

‘Inspector,’ he said, glancing skyward. ‘Look at that. It’s like living in the shadow of Armageddon. We’re in for a soaking this afternoon.’

‘Well, the ducks will like it.’

‘The ducks are welcome to it,’ said Baxter, stifling a yawn. ‘They’re not the ones with rheumatism.’

‘You alright?’ said West. ‘You look done in.’

‘Aye, well, I’ve not had much sleep–’

‘Understandable.’

‘–and I’m running late. So, to what do I owe the pleasure? Is this about the boat?’

‘Actually,’ said West, ‘it’s about your daughter, Rhona.’

‘Rhona? But I’ve just told that young lad everything I know.’

‘Well, once more won’t hurt. Just for me.’

‘No disrespect,’ said Baxter, ‘I mean, I’m happy to have a detective like yourself looking for her, but do you not have more serious crimes to attend to?’

‘This is serious,’ said West. ‘The boys in blue are going to look for her and I am going to try and find out why she disappeared in the first place. That way we might get an idea of where she’s gone.’

‘Well, in that case,’ said Baxter as he opened the door, ‘you’d best come in.’

With his wife under strict instructions to remain in the kitchen lest she intoxicate their guests by breathing on them, Baxter headed for the lounge and pointed West in the direction of the sofa.

‘I’d offer you a tea,’ he said, ‘but–’

‘I know, you’re pushed for time,’ said West. ‘Don’t worry, I’ll be as quick as I can. So, when did you realise Rhona was missing?’

‘Yesterday,’ said Baxter. ‘Maureen went to–’

‘Maureen?’

‘The wife.’

‘Is she here?’

‘Aye, but she’s not up to seeing anyone just now,’ said Baxter. ‘She can’t open her mouth without bursting into tears.’

‘Fair enough,’ said West. ‘Sorry, I interrupted. You were saying.’

‘Oh, aye, Maureen. She called Rhona for breakfast and when she didn’t answer, that’s when she realised she’d gone.’

‘And is that unusual? I mean, for Rhona to go out so early?’

‘Aye. The girl’s happier in her bed than out of it.’

‘But you didn’t call the police, not straight away?’

‘No, no. No point in jumping off the deep end, you know what women are like, probably went to clear her head or something. We waited until lunchtime, or thereabouts, then I went looking for her. Up to the woods, then a drive up the road and back.’

‘But no luck?’

‘No, I even tried the taxi office but they’ve not had any fares up here for weeks.’

‘Did she a leave a note?’ said West. ‘Or a message on your phone, maybe?’

‘Nothing, Inspector, but what I can’t understand is this: if she was of a mind to take a wander, then why did she not take her bag with her? Or her phone?’

‘You mean they’re still here?’

‘Aye, in the den. That’s where she’s been sleeping.’

‘Can we have a look?’

West, still dreaming of the day she’d have her own stone cottage filled with vintage furniture, open fires, and a kitchen with a coal-fired range, was immediately taken by the cosy, antiquated charm of the converted cellar.

‘Blimey,’ she said, ‘this is a right little getaway. I wouldn’t mind hiding down here myself.’

‘Hiding?’

‘Yeah, you know, somewhere where you can cut yourself off from the outside world.’

‘Oh aye, peace and quiet, you mean? It’s ideal for that.’

‘So, if Rhona was sleeping down here, I take it she was just visiting, is that right?’

‘Aye. She said she’d stay a few days, no more, but that was three weeks ago.’

‘Getting under your feet, was she?’

‘Quite the opposite, Inspector. Quite the opposite.’

‘Okay, listen,’ said West, ‘I need to ask a few questions that might sound a bit personal but you don’t have to answer them, if you don’t want to.’

‘What is it you’re wanting to know?’

‘Well, did Rhona have any problems that you know about? Any financial worries, for example?’

Deeming the envelope evidence enough that money was clearly not one his daughter’s problems, Baxter, fearing any mention of its contents would only serve to complicate matters and thereby prolong West’s untimely visit, thought it best left unsaid.

‘No,’ he said bluntly. ‘She’s on a good wage, by all accounts she earns more than most folk.’

‘And no habits? Not fond of the odd drink, perhaps? Drugs?’

‘None.’

‘And what about personally?’ said West. ‘I mean, have you noticed anything odd about her behaviour, does she seem alright in herself?’

‘A wee bit moody,’ said Baxter, ‘but otherwise… no, that’s not strictly true.’

‘Go on.’

‘See here, Inspector, Rhona’s like her mother, she likes to haver, she could talk the hind legs off a donkey, but from the day she arrived, she’s said nothing. She’s kept herself to herself.’

‘Sounds like something’s worrying her. Maybe she’s pregnant.’

‘It’s not that,’ said Baxter.

‘What is it, then?’

‘I wish I knew. We’d not seen her in months, okay? Then she turns up out of the blue, in the middle of the night, if you please. She told Maureen that she’d lost her job and her flat.’

‘Oh well, there you go. That’s enough to send anyone into the depths of depression. She’s probably stressed out about finding somewhere else to live.’

‘That’s not it!’ said Baxter, angrily. ‘She’s a clever lass, she can get whatever she wants. Now, if she was that bothered about finding somewhere to live, she’d have been shoving that blessed com

puter under our noses asking our opinion on the flats she was looking at. And another thing, if she’d lost her flat, then why did she not bring her belongings with her? She was empty-handed, Inspector, not even a suitcase. And why was she not looking for work?’

‘Well,’ said West, trying her best to sound sympathetic, ‘maybe she just needed some time out. Maybe she’s been thinking about a career change, or moving somewhere else.’

‘No, no. I’m telling you, she’s up to something, and whatever it is, she’s keeping it to herself.’

‘What does she do? Work-wise, I mean.’

‘The North West Castle,’ said Baxter. ‘It’s a big, fancy hotel in Stranraer, but I’ve no idea what she does there.’

‘Okay. I’ll give them a bell later and find out why they let her go. What about partners? I take it she’s not married?’

‘No. But she has a boyfriend, I think. A fella by the name of Callum.’

‘Callum what?’

‘Search me. She never said and we never asked.’

‘Do they live together?’

‘As far as I know, Rhona’s always lived alone.’

‘I’ll need her address,’ said West, ‘and Callum’s, too.’

‘Can’t help you there,’ said Baxter, ‘but you could ask him yourself, his number’s on the phone.’

Baxter turned his back, opened the ottoman, and produced his daughter’s handbag and mobile while West, eyeing the half-eaten bowl of crumble lying on the side, snapped on a pair of gloves.

‘Just out of interest,’ she said as she unzipped the bag, ‘did you mention these to the officer who was here earlier?’

‘I did, aye.’

‘And he didn’t ask to see them?’

‘No. Should he have?’

‘Most definitely.’

‘Will I chase after him?’

‘It’s too late for that,’ said West as she rummaged through the bag. ‘Is there anything missing from here? I mean, have you or your wife taken anything out?’

Baxter paused before answering.

‘No,’ he said, clearing his throat, ‘it’s as we found it.’

‘And the phone?’

‘Likewise. You’ll see a number there, the last missed call, that was Maureen. She telephoned Rhona when we realised she was missing.’

‘And you mentioned a computer,’ said West. ‘Is that here, too?’

HUBRIS

HUBRIS